Table of Contents

Introduction

Part I - My most spectacular failure

Part II - Trust must be earned

Part III - We’ve got trust issues

Part IV - Playing in front of your fans

Part V - Trust-raising

Part VI - What it takes

Introduction

The fact that you’re reading this suggests open-mindedness. This bodes well for this eBook, which will argue that to acquire new donors in 2018, 2019, 2020 and beyond, your charity needs to do the opposite of what it’s been doing since the 1970s.

That means a big shift in strategy and processes, but the shift in thinking is quite straightforward. It can be encapsulated in a single principle.

By the final page, you’ll understand this principle well enough to talk about it in team meetings and improve the way your charity acquires new donors.

P.S. Many of the examples used are from Facebook, but this principle applies to all digital channels and, to a lesser extent, the traditional fundraising channels.

Part I - My most spectacular failure

“The coolest workplace ever”

On a Tuesday in 2011, I went to work in the global headquarters of Full Tilt Poker.

I went straight to the breakfast buffet on the first floor, where I toasted a bagel and picked up a smoothie to eat at my desk. I opened my email inbox and checked the lunch menu for that day. The restaurant-standard canteen had served kangaroo steaks and quail pie in my time there, so checking the menu was an enjoyable way to start the day.

I logged on to fulltiltpoker.com, but instead of our website I saw a blank, black screen with the FBI logo in the centre.

The FBI had shut down the website. A federal investigation was underway into money laundering practices in the US, where online poker was illegal.

It didn’t look good.

The CEO circulated a long email saying that everything was going to be fine. I wanted to believe him, but the fact that he could soon be extradited to the US for trial undermined much of what he said.

At one stage, he’d mentioned that the “Alderney gaming license” might be suspended. When I asked my colleagues what Alderney was, they told me it was an island between Britain and France with a population of 2,000 people.

The company was registered there. And the website was hosted on servers on the island. Technically speaking, when people played on Full Tilt Poker, they were playing poker on Alderney.

That was when I knew I had to get out.

My brother, who works for an exciting American tech company, said it was a pity I had to leave the coolest workplace ever.

My first day in the charity sector

I got an interview for an ideal digital marketing role. Except, it was for a charity, and I knew nothing about charities. I’d never even donated to a charity.

But Full Tilt Poker were about to lay off 300+ staff. So when Concern Worldwide offered, I accepted.

My first morning went well. But at lunchtime, I had to pay €5.50 for a chicken-fillet roll and a bottle of water.

That was a bleak lunchtime.

“Fundraising is easy!”

My role at Full Tilt Poker had been solely email marketing. So, given that I didn’t know anything about fundraising, I gravitated towards Concern’s sizeable email list.

By applying what I’d learned in online gambling, I increased the ROI on Concern’s email programme by 582% in the first year.

Fundraising was a strange experience for me. I couldn’t believe that when I sent words and images to people’s inboxes, thousands of euros would flow to Concern without any product or service being exchanged.

To be honest, I thought fundraising was easy.

Blaming Steve Jobs

I’d made progress on the emails, so Concern wanted to hear more digital fundraising ideas. I told them we needed a “digital-first campaign”. And I was emphatic about this, as I’d read about such campaigns many times on the internet.

My pitch went something like this:

“We need a piece of digital content that is beautiful and exciting. We need a jaw-dropping video that people can’t help but watch and share with others.”

Copying Charity: Water

I got sign-off for a video campaign that would go out on Facebook, Twitter and email.

At the time, I was in love with Charity: Water’s videos. They were shot with flair. So I trawled their website and found a link to the website of a freelance videographer who had been shooting their videos for years.

I rang him and got a quote.

I justified flying him over from California by saying that if Charity: Water could raise millions thanks to one of his videos, surely we could raise €60,000.

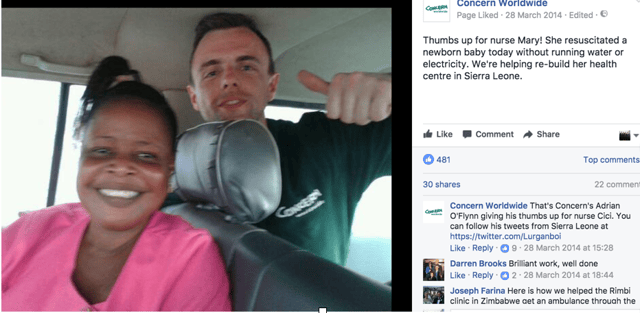

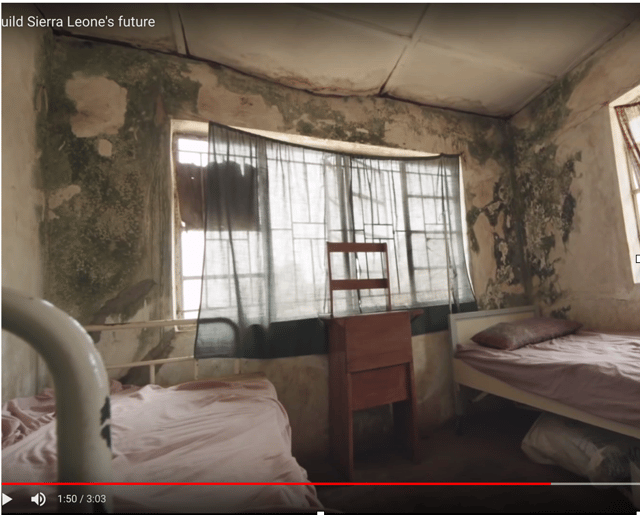

A walking saint

We found our leading lady just outside Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone. Her name was Nurse Mary K. Cole. She’d been running a local health centre for over 20 years. The place was falling apart and the internal walls were covered in a thick, green mould. To me, it looked more like an abandoned farm building than a hospital.

I posted this the day I met her:

When a sick child needed medicine that the government didn’t provide, she bought it with her money from her own. I could go on and on about her… I’d never met a walking saint before.

By the time we left Sierra Leone, I desperately wanted to raise the money to rebuild this place:

No new health centre for Nurse Mary

Then, after all the editing, late evenings and optimism-fuelled meetings, the video went live.

Plenty of people watched it, but almost nobody donated.

We got a few grand from existing donors via email (which probably would have come in without the video).

The YouTube analytics proved it was the best video Concern had. Most people watched it through to the end, but that wasn’t much use to the men and women who sat with me in Freetown and talked about the family members they’d lost to that sub-standard shithole.

The worst feeling

The campaign fell flat on its face and lay there while the rest of the world rumbled on around it.

Professionally, there’s nothing worse than that feeling.

I’d promised Nurse Mary I’d help her rebuild her health centre. Yet while she was over there saving lives without electricity or running water, I had endless supplies of both, and a laptop and a budget and the support of an entire first-world organisation – and what had I done?

Essentially, I’d done nothing except spend donors’ hard-earned money.

Suddenly, fundraising didn’t seem so easy.

And that feeling is de-motivating. It discourages you from trying more new things. It makes it easy to simply go to work, process your inbox, attend the meetings you’re invited to, deliver what’s requested of you and go home.

But then I’d feel anxious. I’d have this inescapable sense that I was wasting my professional life raising POs and typing results into Excel sheets, when I should be doing something more impactful.

Even though the lessons learned from this failure would prove invaluable to me later on, I had no idea what to try next. So I handed in my notice.

Accidentally becoming a freelancer

Around the same time, a few high-profile scandals had rocked the Irish public’s confidence in the charity sector:

A third of the public’s trust had evaporated.

I became more and more convinced that Ireland needed a charity-rating website like Charity Navigator. While working at Concern, I’d also been organising hackathons to gather charities’ financial data. I’d set up a company called Where Donations Go. So when the digital fundraising was getting the better of me, I decided to give that a shot.

I never found a funder for Where Donations Go. But one day my phone rang and an agency I used to work with asked me to work on a social media strategy for a non-profit client.

A few weeks later, the Irish Heart Foundation asked me to work on a digital event for them, and suddenly, I was a freelancer.

Part II - Trust must be earned

What do I have to offer?

I hadn’t been able to acquire new donors, but there was one thing I’d worked on at Concern that had worked strangely well on Facebook.

Actually, it was four things:

This is what worked.

When we thanked our followers for changing one person’s life, our engagement soared.

Engagement seemed to breed more engagement. When Achoyo reached over 100,000 people, free of charge, I knew we were onto something.

When I looked at the year-on-year figures, I was in disbelief. The same number of posts, with little or no promotion, had increased our engagement by 1842% in one year.

I presented this at a conference in Dublin, and Facebook themselves were impressed. They invited me to deliver a keynote at a Facebook conference in London, and put our story up on their website as a success story.

So, as a freelancer, I sold this experience to potential clients and ended up doing a lot of work on Facebook content.

Stumbling across success

I continued to find and edit succinct impact stories that went on to reach large numbers of people, for free, on Facebook.

For a while, I told people (and myself) that I specialised in turning charity Facebook pages around.

But then two things happened that changed what I thought about digital fundraising, permanently.

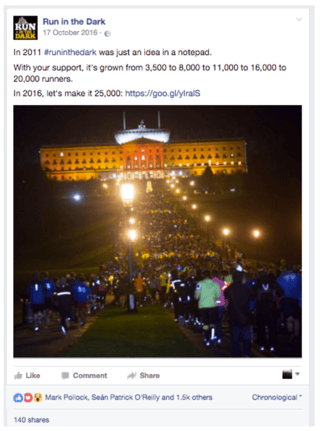

This first was this post for a fundraising event called Run in the Dark.

After clicking through the link in this post, 532 people paid their registration fee. I was stunned.

How had this happened? The post is good...but it’s not that good!

To understand this result, you need to see the inspirational, cause-related posts that went before it. For weeks I'd been putting up posts like this:

It seemed the key to getting people to respond to an ask on Facebook was to emotionally involve them in the cause before the ask arrived.

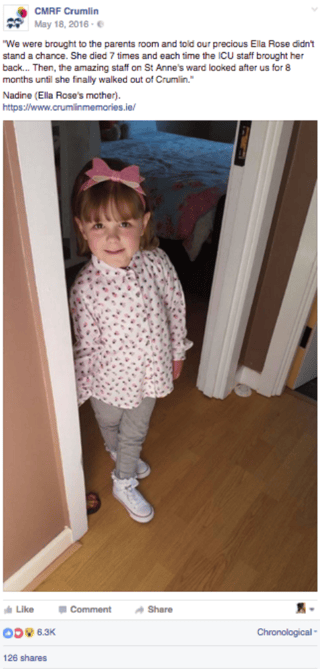

This hypothesis was verified a month later when a children’s charity I’d been working with for months put up a post asking people to host a Christmas Jumper Day.

Over 100 new schools and businesses signed up!

They raised over €60,000 and doubled their schools database, a success story that was highlighted by Facebook on their global non-profits page.

Again though, the supporters already had stories like this languishing in the back of their minds:

This makes sense though. It’s so much easier to champion a cause in your workplace when you can imagine the money you’re raising bringing Ella Rose back to life seven times.

Trust must be earned.

And it must be earned before you ask for money.

Could it be magic?

This conclusion went against the common practices in fundraising. So I looked outside the blogs and echo chambers I inhabited to see what I could dig up on the subject of trust.

And to make sense of these seemingly magical fundraising results.

We’re not as rational as we think

My friend Mark is the Brand Manager for a sports nutrition company. He’s responsible for about €20m of revenue across 15 countries. When I told him about my trust-building theory, he laughed in my face.

Then he said, “What do you think branding is?”

I mumbled something about products and identity, before he added:

“It’s shaping the way people see the world around them, so that when it comes to picking a product, they pick yours.”

He recommended a book that said the same thing in a more comprehensive manner.

The book was called Buyology, and it described how brands get customers to associate their brands with good feelings or emotions.

Neuroscience has proven that the majority of buying decisions are subconscious. We make what feel like quick, conscious decisions to buy things, but the decisions are actually based on associations and connections made long ago at a subconscious level.

The charity equivalent of this is telling stories that emotionally involve people in your cause, so that when you ask them to donate they’re not thinking about their bank balance, they’re not wondering what your salary is, they’re thinking about the stories you’ve already told them.

The emotion is already there, bubbling beneath the surface...waiting for the right ask.

Money is a trust-based system

Mark also told me that anyone who’s working in any kind of communications role should read Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind.

At one stage in this phenomenal book, Yuval Noah Harari explains how the concept of money came about:

“There have been many types of money. The most familiar is the coin. Yet money existed long before the invention of coinage. Cultures have prospered using other things as currency, such as shells, cattle skins, salt and beads. In modern prisons, cigarettes serve as money.”

“Money is a universal medium of exchange that enables people to convert everything into almost anything else.”

“How does money work? Cowry shells and dollars have value only in our common imagination. In other words, money isn’t a material reality, it is a psychological construct.”

“But why does it succeed? Money is a system of mutual trust, based on two universal principles:

With money as a go-between, any two people can cooperate on any project.”

And that’s exactly what fundraisers do, isn’t it? We use money as a go-between so donors and charities can cooperate on projects.

Your targets may be stated in money, but money is just a measurement of the trust required for cooperation.

Fundraising is a system of mutual trust.

Doubting social institutions

Every year, the PR firm Edelman asks people in 25 countries if they trust their social institutions (i.e. businesses, government, the media and NGOs).

Ireland, Britain and the US have all had double-figure drops in the past four years.

In 2013:

Ireland: 46% trust in institutions

Britain: 53%

US: 59%

In 2017:

Ireland: 35% trust in institutions

Britain: 37%

US: 47%

We’ve got trust issues alright. People question everything now.

We make shortlists for everything

A display advertising company called Quantcast carried out an enormous piece of research on consumers’ buying habits. They interviewed thousands of people in Australia, France, Germany, Italy, the UK and the US. They asked them questions about eight different industries and found out something very interesting.

Humans have shortlists in their minds, and 80% of the time they buy a shortlisted product.

Across all these countries, and for products as diverse as health insurance, groceries, cars and smartphones, the same result came up again and again.

When a person decides they need to buy something, they don’t research every single product in that category. Instead, they have two or three options in mind and evaluate those. The world is simply too complicated to review every category for every purchase. Nobody ever gets to the end of their search results on Amazon.

People are bombarded by endless options in every category. They use shortlists as a coping mechanism.

So only one out of every five purchases goes to a brand that hadn’t already established itself in the mind of the consumer.

In other words, four out of every five purchases goes to a brand that has already established trust.

This, of course, applies to charities too. Anyone who’s looked at the website traffic for charities’ About Us or Annual Report pages knows that people don’t research and compare charities.

So it’s likely that of the millions of donations that will be made on charity websites next December, 80% are decided on long before the Christmas campaigns are launched.

If you haven’t been doing the difficult work of building trust and making it onto people’s shortlists, you’ll be left fighting for the fickle 20% that are leftover.

When you sit with a beneficiary

You remember…

All the email debates and meeting fatigue and never-ending to-do lists fall from your head. You remember why you’re doing this. You see things as they do. It’s as if the beneficiary helps you access a part of your personality that you just don’t access enough…the humble-kindness part that gets crowded out by all the things that comprise your routine.

And if that happens to you while you work for a charity, just imagine how crowded out the humble-kindness part of warehouse managers, dentists and German teachers is. It’s going to take a lot of digital sit-downs with beneficiaries to uncover it.

Twenty-six regular givers in Waterford

According to Irish fundraising folklore… the first on-street fundraiser to travel to Waterford, a seaside town in the South of Ireland, signed up twenty-six regular givers in one day.

If the same guy went to Waterford tomorrow he’d struggle to get two.

The first online banner ad had a click-thru rate of 94%. Now, 0.10% is deemed a success.

There was a time when everyone opened 100% of their emails.

But what happens? Effective tactics are exhausted and, eventually, ignored. The same rule applies to all new marketing channels, and response rates decline as the public catches on. But the exceptions to this rule are the people who trust you.

Think of it this way: What’s your open-rate for emails from ex-colleagues? When was the last time you deleted an email from a person you’ve had a face-to-face conversation with without even reading it?

Yes, the modern consumer is adept at putting their guard up and filtering out everything that doesn’t immediately relate to them. But the relevant things still get through.

They see the things they want to see.

Because of this, you end up with two groups of people. Those who trust you and those who don’t. Those who stop to read your Facebook posts or open your emails and those who scroll on by.

This is why retention is so easy and acquisition is so hard.

Part IV - Playing in front of your fans

Home vs away

Betting companies have a weighted formula that alters a team’s odds of winning a sporting fixture. One of the factors they input is how far a team has to travel to play the game.

So a team could be 2/1 to win at home, but 3/1 to win against the same team if they have to travel 100 miles to play the game, 4/1 if they have to travel 300 miles, and so on.

Logically, this shouldn’t be the case. The rules are the same. The pitch sizes don’t change much. But anyone that’s played sport or supported a team knows that playing in front of your own fans is just a different ball game.

Digital fundraising works in much the same way. The further you go from your own fans, the less likely you are to secure a win.

What I learned in the British Midlands

I once ran fundraising ads to two groups of 10,000 people in the British Midlands:

Both groups were females.

Both groups were 45+.

Both groups had Liked overseas aid charities.

The only difference was that one of the groups had Liked the overseas aid charity that I was working for. That warm group won the test, no surprises there. But the margin of victory stunned everybody involved.

The cost-per-acquisition was ten times lower for a person who had Liked the charity’s Facebook page.

That’s the surprising value of targeting the people who already trust and support and like your charity.

How do you define a fan?

Anyone who has engaged with you on social media, visited your website or signed up to your email list.

A fan doesn’t have to be a die-hard, life-long fan. Not everyone who cheers when Manchester United score is a season-ticket holder at Old Trafford, but they still consider themselves fans.

Seth’s description of fundraising

Seth Godin is to digital marketing what Usain Bolt is to sprinting. He’s so much better at it than everybody else that it’s just fun…it’s enjoyable for everyone to experience.

This is what he says charities should do:

“Turn strangers into friends, turn friends into donors and turn donors into fundraisers.”

As a sector, we just want to turn strangers into donors.

We skip the friendship stage.

Fundraising on digital or digital fundraising

The word fundraising carries with it a set of assumptions and meanings that have built up over entire careers. The semantics are important here, because the verb fundraise implies that your sole objective is to raise funds.

With that objective as their starting point, charities have tried to fundraise on digital (i.e. they’ve sought to apply the principles of fundraising to digital channels).

But digital is a new environment, with new rules of engagement. So charities should seek to understand the principles of digital, then apply those to fundraising.

It took me a long time to realise this.

But once I saw that I (and basically the entire charity sector) had this the wrong way round, I was annoyed.

Why? Because I’d already worked on the solution.

I’d seen it up close. But I hadn’t put two and two together because I thought digital fundraising and digital gambling were fundamentally different…but they’re not.

The same principles apply.

What Full Tilt Poker knew

Full Tilt Poker acquired over 11,000,000 online poker players in nine years. By the time I went to work for them in 2011, they had digital acquisition figured out.

The only communications channel they had was email.

The database was split into two broad segments, called Depositors and Non-depositors. People who had deposited money into their poker accounts and people who hadn’t (a bit like donors and prospects on your database).

These two groups received similar emails but with different asks. The Depositor emails asked people to play poker for real money. But the Non-depositors emails just asked people to play poker.

For example, there were free tournaments that Non-depositors could enter for free and, if they got to the final stages, they could win money.

The primary objective of the Non-depositors emails wasn’t to get them to generate income. It was to get people playing on Full Tilt Poker’s website. It was to make them comfortable with the website, to familiarise them, so that when they wanted to play for real money, Full Tilt was the logical choice.

Using this approach, they acquired millions of players.

What Full Tilt Poker knew, which most of their competitors and most charities didn’t, is that digital acquisition is a two-step process.

Their initial objective was to build trust. Once that was done, they asked people to play poker for money.

“Their email list is, like, INSANE!”

In the back of a big, white Jeep, bouncing through the back-end of Sierra Leone, I began asking Paul, the American videographer, about Charity: Water. Much of what he said was interesting, but one thing he said stood out.

Yep, their email list is insane.

The September campaign video and webpage that I’d been imitating from the front-end was only part of the reason they could raise a few million dollars in one month.

In a recent podcast interview, Scott Harrison talked about how before he started Charity: Water he already had an email list of 15,000 young New Yorkers from his nightclub promotion days.

He made a good living off that email list for over a decade. He knew the power of an email list of people who trust you long before he started Charity: Water.

I overlooked something when I was drooling over their $2m income, which is obvious when you look at their YouTube channel:

They’d been building trust within their target audience for years.

One foul swoop

My spectacular failure occurred because I tried to do in one swoop what Scott Harrison had spent a decade on.

I just assumed that was how digital fundraising worked. Why? Because that’s how traditional fundraising channels worked.

And if you’ve been around the fundraising block a few times, I bet you’ve already seen just how foul singular swoops can be on digital.

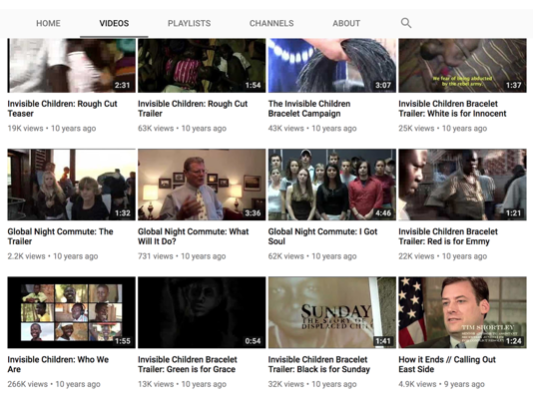

Kony 2006

Everybody remembers the morally questionable viral success of Kony 2012.

But most people don’t realise that Invisible Children had been producing high-quality videos since 2007.

If you go to their YouTube channel and select “Sort by oldest”, this is what you’ll see:

The most revealing video is in the bottom left, “Invisible Children: Who We Are”.

It has 266,000 views and explains how, in 2006, these three talented videographers took their documentary “Invisible Children” on a national tour. They inspired 80,000 young people to sleep overnight in their town centres because that’s what children in Uganda had to do to avoid Kony.

Yes, Kony 2012 went viral, but Kony 2006, Kony 2007, Kony 2008, Kony 2009, Kony 2010 and Kony 2011 provided the launchpad of warm, trusting fans.

Your fans have their own fans

The youth of today may be harder to win over. However, keep in mind that they have their own fan bases. Dozens and dozens of people who trust their judgement more than they’ll ever trust a charity.

That’s the pay-off.

But there’s a but...

But because charities have successfully used a fundraise first, trust second approach for decades, a change of culture is required.

And changing an organisation’s culture while it’s in motion and striving to hit its targets is not easy.

An awkward word

It’s fitting, though. It represents an awkward reality.

Forcing trust into fundraising is not going to be easy, and this section explains why. (It’s more practical and pragmatic, but please don’t skip it, we need to be realistic about the challenges too.)

Figuratively speaking

They say that the figures speak for themselves but right now, for charities, I don’t think they do. The figures speak for pensioners and a loyal band of donors whose trust was earned long ago.

But it’s hard to argue with the figures, especially in fundraising.

Demographic differences

When I go to fundraising conferences, I hear a lot of broad, confident statements about how to communicate to your donors. And I sit there wondering what would happen if I showed my Facebook ad results to these speakers. Would they be as sure of themselves if they saw the difference in how under-45s, 45–64 year olds and over-65s responded to the same message?

Prescribing a one-size-fits-all approach suggests they don’t know how great the demographic differences are.

And there are almost certainly people in your organisation who underestimate this.

“Income is down, but…”

Your income won’t drop like a stone. Darkness won’t suddenly descend upon thy fundraising. The reservoirs of trust that you’ve built up in the minds of your donors will keep you going.

The effect will be more gradual. A few grand here…a campaign ceased there.

Theories will be put forward to explain why the old fundraise-first approach isn’t working. Amidst all the post-rationalising and meetings and article-forwarding, it will be easy to lose sight of the simple, indisputable trend.

The imperative for change

Separate to what your boss wants or what your friend wants or what your mortgage lender wants… is what the world needs.

The very fact that you’re still working for a charity indicates a healthy disregard for those narrow desires and an awareness of a bigger picture.

So this is a direct plea to you.

If charities don’t change the way they communicate with and acquire new donors, many of them will cease to exist.

This is a major problem. Why? Because the world needs organisations that tackle stupidly complex problems. We need organisations that pursue hopeless causes (which for-profit companies would never touch) just because that’s the right thing to do.

So, the world needs fundraising professionals who are tenacious and strategic enough to navigate this new environment. Fundraisers who realise that we can’t just sit around like travel agents, hoping the web will stop ruining their model. Fundraisers who can drag, cajole and inspire their colleagues through the pain of change to establish a new way.

Servicing the churn

The suggestion that your job is to manage decline should bother you.

The sense that your role is to top-up the attrition of your charity’s database should make you uneasy.

The belief that all the growth happened years ago, in the heyday of fundraising, is a lie people choose to believe so they don’t have to take any risks. It creates a comfortable zone to work in from Monday to Friday. It allows fundraising teams to go home without a care in the world.

While elsewhere, in the same world, others must suffer through their weekends because a fundraising team is unwilling to question the status quo.

A feeling you should watch out for

It catches you off guard on a Friday afternoon or in the silence of the office before everyone else gets there. It’s stimulated at conferences and, in a lesser way, by thoughtful articles. It’s the part of you that wants to explore and learn and experiment, rearing its beautiful head.

But most of the time it gets squashed by your to-do list, as the logical part of your brain latches onto tangible and imminent tasks.

In under-resourced charities, where single roles are stretched across multiple job functions, the to-do list never ends.

It’s all reactive. It’s all execution. But progress requires you to be proactive. It requires planning. And if you want to have a real impact on your charity’s services, you need to listen to that feeling.

You need to take a break from executing old plans so that you can develop new ones.

P.S. I know this isn’t digital fundraising. But f*ck it. I believe this is crucial.

The calendar is a Merry Go Round

The Merry Go Round is always on. It’s noisy and always moving. But despite all that movement and energy, it’s not going anywhere.

This particular Merry Go Round never stops. There’s always a big appeal or a pre-agreed deadline looming.

Stepping off that Merry Go Round, as it’s moving, takes a unique type of courage.

It takes calculated bravery. You know it could look daft. You could fail. But you do it anyway, because you know where the Merry Go Round is going.

It’s not make or break, yet

But when it is, everything in this section will still apply. It will take time and multiple meetings to change the way you acquire new donors. Which is why you should start before everybody becomes panicky and demanding.

There’s no getting around it

Charities need to fundamentally change the way they acquire new donors. But charities aren’t going to change themselves. The stimulus needs to come from individuals with the necessary insight and persistence.

If you’re up for it, the next section contains points and ideas that will help you do this.

Part VI - What it takes

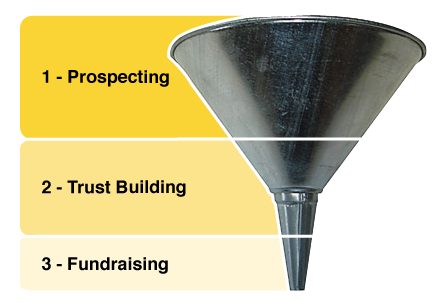

It takes a well-planned fundraising funnel

The funnel we use has three stages:

There are many convoluted explanations of marketing / fundraising funnels online, but essentially, the funnel reminds us not to ask for money all the time.

It forces us to consider the wary, uncertain donor’s point-of-view. And reminds us to do things that educate, inform and intrigue them.

Strategic Alignment

In most charities, separate fundraising campaigns and events are given separate targets. And often hire different agencies to try and do the same thing.

This is a hangover from the last century, when independent campaigns could appear from nowhere and acquire donors.

Now, to build trust and acquire donors is a consistent manner, your budgets and targets must be aligned. You must invested budget and resources in the top of the funnel, the middle of the funnel and the direct-response fundraising asks at the bottom.

Lead Generation

The popularity of online campaigning websites like Care2 and Change.org illustrates an opportunity for charities. People are willing to give the contact details to causes they care about, if the ask is simple makes them feel involved them in the cause.

This should be a big part of your fundraising funnel.

Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn all have lead generation features in their advertising options which make it easier than ever to try this.

I particularly recommend targeting people who have engaged with your charity or cause on Facebook with Facebook Lead Ads. I’ve had some spectacular results creating Facebook-petitions with this tool.

If you’re organisation don’t do petitions, you should petition them to start!

One website-hit wonders

You’ve seen how jumpy people are on their smartphones. They flit from here to their and chase whims with their thumbs.

When Facebook analysed all the results on their platform (billions of advertising spend, across every industry) they found that, on average, people converted on their 3rd website visit.

There are some one website-hit wonders, but for the vast majority, it takes multiple website hits or visits before they take out their credit card.

So you need a plan that aims to get people to your website at least three times.

Re-targeting

Re-target people who have:

Re-target them with social ads, display ads and any other campaigns you’re running.

One easy (lazy) tactic that works

One thing that anyone reading this can do is to set up an automated welcome journey via email.

Take 15 of the strongest emails (or direct mails, or Facebook posts, or videos) that you’ve used over the last few years, ideally content that has already had people clicking and/or donating.

Arrange them into a series that begins with impact stories (the work you’ve already done) and moves towards fundraising (the work you intend to do).

That way you can build trust and fundraise all in one journey.

Tools like MailChimp make this shockingly easy to do.

High-volume digital communications

Direct mail is expensive to send. So charities adopt a high-cost, low-volume approach, sending six to eight pieces a year and making sure each one has a good response rate.

But most digital channels are the exact opposite of direct mail. The cost of “sending” on digital is extremely low.

Unfortunately, the response rates are also low. Faced with this issue, most charities make one of these two mistakes:

A really good email will have a conversion rate of 0.2%. If you’ve an email list of 10,000, that’s 20 donors. The mistake here is that they only send emails when they’re sending DMs, and then conclude that email doesn’t work for them. They apply the low-volume approach that worked for DM and blame email when it doesn’t work.

They achieve high volume, but they post some of the most boring, localised and self-absorbed messages the internet has ever seen.

The solution is a high-volume communications applied as part of a year-round, always-on, digital fundraising approach.

But the stories you communicate must be good.

Consistency

If you take nothing else from this eBook, write this line down somewhere:

Success on digital will require consistent effort, resources and testing.

Starting and stopping and starting will get you nowhere.

A game of inches

One of the reasons that a stop-start approach will get you nowhere is that you need to continuously improve and optimise your communications.

With that in mind, this is the fundraising version of the most clichéd, over-used sporting speech of all time. Al Pacino delivers it before the finale of Any Given Sunday, and it’s known as “The Inches Speech”.

“You know when you get old in fundraising,

channels get taken from you.

That’s, part of life.

But,

you only learn that when you start losing stuff.

You find out that life is just a game of inches.

So is fundraising.

Because in either game

life or fundraising

the margin for error is so small.

I mean

one ad too late or too early

you don't quite make it.

One Call-to-action too slow or too fast

and they don't quite click it.

The inches we need are everywhere around us.

They’re in every broken campaign

every image, every headline.

On this fundraising team, we fight for that inch.

Cos we know

when we add up all those inches

that's gonna make the f*cking difference

between WINNING and LOSING

between people LIVING and people DYING.”

Some alliterative personas

A persona is an imaginary person who represents a demographic. For example, a hospital I work with target “Visitor Veras”. These are older women who live within 30 km of the hospital and are likely to have visited the hospital when a friend or relative was sick.

This makes a surprising difference. Having a specific persona focuses the mind and results in better stories being gathered and told.

It takes time and patience

You’re not going to like this one. It might even make you want to abandon this eBook and call me a salesman, but here it is...here is how digital growth works:

Your ROI should be quite underwhelming in Year 1.

This is hard to accept because fundraising (rightly) comes under scrutiny by finance departments and boards to ensure they are spending money wisely. When mass-marketing tactics still worked, this was fine. You could roll the dice and tell finance what number you got.

However, establishing the trust of individuals takes time, especially on 2.5-inch-wide screens.

But as we saw in section IV, once you’ve built a fanbase everything is different.

How to get paid $2,079.50 to make a few pancakes

Because the previous section was so likely to make you dubious, I’m going to back it up with an impressive example.

In 2011, Lindsay Ostrom, a fourth-grade teacher in Minnesota, started a food blog called Pinch of Yum. Every day she cooked something and posted a recipe and some pictures on her blog. Then she put a post on Instagram, Facebook and Pinterest.

That was her I. That was her daily Investment. One recipe and three social media posts.

The difference between Lindsay and other bloggers was diligence.

She made the same unspectacular Investment every day for five years. One recipe and three social posts, every day.

But Lindsay did do something spectacular. She published her R (her Return) every month (her Net Profit). It was an experiment to find out if you really could make money from a blog. Here are the results:

In month 1 her Return was $21.97

In month 6 her Return was $216.60

In month 12 her Return was $2,797.02

In month 24 her Return was $7,084.50

In month 36 her Return was $26,385.75

In month 60 her Return was $62,385.10

She left her job as a teacher around month 30.

The same daily investment made her an internet millionaire. As her followers grew organically and consistently, the people who trusted Liked and shared and talked about her blog.

She started got more and more R for the same I.

We can see that clearly when we look at her ROI in terms of what she earned per recipe:

In month 1 her ROI was $0.73 per recipe

In month 6 her ROI was $7.22 per recipe

In month 12 her ROI was $93.23 per recipe

In month 24 her ROI was $236.15 per recipe

In month 36 her ROI was $879.52 per recipe

In month 60 her ROI was $2,079.50 per recipe

So the answer to the question of how to get paid two grand to make a few pancakes is something that Lindsay and other professional food bloggers call “1% infinity”. The conclusion they reached on a podcast on this subject is that 1% growth, every day, leads to infinite growth.

So, you should pursue 1% growth, not an immediate return on your investment.

P.S. If you’re still not buying it, here is (one of my favourite images on the web) her traffic growth on Google analytics over those five years.

You (almost) need to make them think it was their idea

Stop telling people what to do all the time and tell them more success stories.

Tell them gripping tales of the people you’ve helped overcome adversity. Tell them about situations that they’ve never known. Help them imagine what it’s like. Gradually draw them in to your cause. And then one day they’ll open their inbox and think:

“ I’ve decided that I like this charity’s work. And I am going to give them some of my money.”

Get your stories straight

I think the storytelling principles are crucial. So crucial, in fact, that I made this point in my company name.

When all the effective tactics have been shared and the dust has settled on the digital frontier, I believe it will be storytelling that sets the successful fundraising teams apart.

So I’m going to share a few things I’ve learned from studying the world’s best storytellers (screenwriters and novelists).

Stories are about change

Vince Gilligan, the creator of Breaking Bad, said that the problem with most TV shows is that once they’re successful, the networks want them to run forever. So they keep the characters as they are and try to come up with more and more scenarios to put them in. So when he took a chemistry teacher and turned him into a drug baron, it became one of the most popular TV shows of all time.

Robert McKee, the storytelling guru of Hollywood, says:

“If there’s no change in a story, then the audience feels nothing.”

This is the reason storytelling is so effective for charities. The sole reason charities exist is to create change.

You need to tell more stories about the change you’ve already made in the world. If you can do this, people will want to hear more from you, not less.

What it doesn’t take

None of these are stories of change.

“We’re hosting a coffee morning somewhere.”

“Look at what our CEO is doing today.”

“Read this article on The Guardian’s website.”

“Life in this country is still really terrible.”

“This company gave us 0.008% of their net profit on a big fake cheque.”

“Buy a raffle ticket.”

They don’t do your organisation’s work justice.

Nobody cares about your charity

But there’s a part of them, buried deep down, that can’t help but care about your beneficiaries… especially when they overcome insurmountable odds and get to live an improved life.

That’s something we all can relate to. Those stories are inspirational.

The storytelling principles of Robert McKee

They are vast. His book Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting runs to 466 pages. But I urge you to read the first 216 of those pages.

In my opinion, that is the best career move you could make right now.

What Kurt knew

Every fundraiser understands the importance of good stories, but most charities have specialised in telling one type of story when there are six different types.

In 1995, the writer Kurt Vonnegut gave a presentation called The Shapes of Stories (which is on YouTube) and explained that all popular stories fit into a few simple emotional arcs.

Fast forward to 2016, and the Computational Story Lab at the University of Vermont has proven, without a doubt, that Vonnegut was correct.

They used software that analyses the positive and negative sentiment of words to analyse 1,300 classic novels. The researchers found that all stories fell into six emotional arcs. They named them as follows:

Most fundraising appeals are (and should be) a tragedy. They will get the best response rate. But that doesn’t mean they are the only stories charities should tell.

As you saw from the screenshots in Part II, we’ve had startling success with rags to riches and man in a hole.

People really respond to them, and they help people connect with the work you do. They’re powerful, underused tools.

Tragedies

I don’t want any hard-core direct marketers to misinterpret the previous section. I know that hard-hitting, uncomfortable tragedies are what open people’s hearts and wallets.

I’m just saying you need to vary your stories and do more work to set up that tragic appeal.

Making magic happen on Facebook

When you’re telling a rags-to-riches (not literal riches; the riches could be good health, for example) story on Facebook, give your donors the credit for turning things around.

Your name is in the top-left of the post already, so you don’t need to be self-congratulatory and mention yourself again.

For example:

This is the difference BRAND’s work has made in Noah’s life = 35 Likes

This is the difference you’ve made in Noah’s life = 80 Likes

So just do this:

It’s a magic formula. And it doesn’t just apply to Facebook.

Fictitious descriptions

Third-person accounts written by somebody who wasn’t there have a way of sounding hollow. They tend towards the banal and clichéd because our imaginations are so puny compared to the complexity of reality.

Stories are better when told in a person’s own words.

That rawness is hard to replicate.

So one of the best things you can do is to start interviewing your beneficiaries more often. If you get people talking about 1) and 3) from the previous section, you’ll get really strong stories.

Magnifying it

If you could take a magnifying glass to one part of your multi-faceted organisation to show all your donors one single thing…what would it be?

I think it should be a smile. A smile that your donors put on the face of somebody who needed help.

Reserving judgement

Try to be more aware of your preconceptions.

Try to let your supporters shape your content strategy more than your colleagues do.

Try to accept that you don’t know what the best headline is.

Try to accept that you don’t know which image will catch people’s attention.

Try to set-up small, cheap tests to find out what you don’t know (see the previous two points).

And even if you don’t do any of these things, try to put aside some time to form new judgements.

Wielding light

You wield light. If you shine that light on the right things often enough you’ll change people’s lives. And not just your beneficiaries’ lives.

There are no perfect happy endings

But charities don’t exist to create perfect happy endings. Charities exist to change lives for the better.

Show that change more often, even if it’s not perfect.

It takes some vision

It’s challenging, but step away from your spreadsheets and slide-decks for an hour and look at the way the web is making us all more connected.

You’ll see that an opportunity exists for our generation of fundraisers that wasn’t there for the last generation. An opportunity to cure diseases and educate. An opportunity to save the lives of children who deserve to be saved. An opportunity to protect the rights of humans who deserve to be protected.

It’s not easy, but it’s possible.

A ten-word summary of Trust First, Fundraise Second

Show change. Prove your cause is worthwhile. Then ask for money.

THE END